|

Adilov Sirojiddin, left, and Otabek Djuraev, are two bloggers in Uzbekistan who are pushing for free speech in their country. Meet the defenders of free speech in Uzbekistan: Gonzo-style bloggers. These are the folks who are testing the redlines of what writers and videographers in this country can report and post. These bloggers aggressively film wrongdoing, take up causes of people who pay them as well as those they feel driven to defend. They tend to be more outspoken and brazen than most journalists here.

Bloggers in Uzbekistan are a hybrid of western bloggers and influencers. While bloggers in the U.S. mostly write commentary and influencers mostly hawk products, here bloggers maintain popular news channels on social media, especially Telegram and Youtube, many with paid advertisements. The worst kind of bloggers here blackmail and extort people to pay them so that they don't post embarrassing videos or report about their corruption. The case of Otabek Sattoriy, a blogger convicted last year of defamation and extortion and now serving a six-and-a-half-year prison sentence, illustrates the tension between sanctioned (ie. controlled) journalism and rogue bloggers. On Wednesday, Sattoriy's appeal was heard in the Uzbekistan Supreme Court. His three lawyers each presented arguments that Sattoriy was exposing corruption and said the government's case against him was trumped up to stop his aggressive reporting. The three judge panel is reviewing the lawyers' arguments and will announce their decision next week. I'm told that Sattoriy's lower court hearings drew hordes of journalists. So I was surprised that there were less than a dozen media and mostly bloggers at Sattoriy's Supreme Court hearing. "We came because we want to prevent future cases for ourselves and other bloggers," explained Adilov Sirojiddin, a Youtube blogger with over 400,000 subscribers. He's also a reporter for Ezgulik, a human rights group. "If he’s made a mistake, we want to learn from this. There should be transparency in our country. We should be able to openly speak as journalists and bloggers and no prosecutors should prosecute us." There are no protections for bloggers in this country. The Agency for Mass Media—aka the government censors— dismiss bloggers as "active citizens." "There is nothing about bloggers in the legislation," Mamurjon Parpiev, head of media development at The Agency, told me. "Everyone who owns a telephone is a potential blogger. Thirty million people in Uzbekistan could be potential bloggers." Most bloggers here make the bulk of their money through advertisements on Youtube channels. In the past, most of those advertisements came from Russia, but with sanctions most Russian advertisements have stopped. "Bloggers are for sensation, loud speak. Others are looking for shock," Sirojiddin explains. "Those covering this hearing today are interested in the fate of Sattoriy. No one is paying us to be here." Otabek Djuraev, a Youtube blogger who has 352,000 followers, sees bloggers as more altruist, a kind of paid advocate. "Bloggers help people with basic problems," he said. "Bloggers get results for people who need help. I have helped many people because I can write what I want and I don't have to turn my story into a head editor who can kill it." I'm hearing a lot about editors in this country who kill stories because of threats from the security services (think Russian-styled KGB) in this country. And I'm hearing from journalists who are tired of fighting with such editors to get stories published. Djuraev and Sirojiddin say they don't hide that they ask for support from "businessmen and rich people." They are self-financed and pay for their own equipment, travel, hotel and fuel costs to cover stories all over the country. They argue that journalists have their own agendas and censor coverage, while bloggers stream entire events, providing hours of coverage. I found this to be true when I discovered that Sirojiddin posted an excruciatingly boring 12-minute video of me interviewing bloggers. Within 20 hours the post had 112 comments and more than 4,000 views. Many comments expressed bold, anti-government sentiments. If you want, you can check out the video here. Official journalists argue that these bloggers are not trained; they don't know the ethics of journalism; "it's just a business." This argument strikes me as hypocritical because editors at some of the most popular media sites regularly kill stories they fear will upset the government in order to stay in business—to keep making money. The government has taken several media outlets offline for days in the past and its security service routinely asks investigative reporters for "friendly chats." (More about this in a future post.) Some journalists here sympathize with editors who are pressured by the security services. This is the way it is in Uzbekistan, they argue. But I've interviewed many brave journalists in other post-Soviet countries with more draconian media restrictions—places like Belarus and Azerbaijan— who continue to report the truth even though they are regularly followed, harassed by the government and even imprisoned. Djuraev says he continues to writes what he believes is the truth even though he says he's been summoned to the prosecutor's office three times. My translator, Askar Djuraev, explained it this way: "When you think of journalists in this country, you think of people who work for the state. But bloggers are independent. They tell the truth." Many lawyers are afraid to take the cases of arrested bloggers and activists in Uzbekistan, but not Umidbek Davlatov. "I'm not intimidated," he told me. He said the only time he felt really threatened was when he handled the case an American citizen who was charged with terrorism. "Law enforcement tried to intimidate me. They took me into a separate room and threatened me." Afterwards, Davlatov revealed in a media interview what had happened. Davlatov got his client's charges reduced to a $50 fine and he was released.

He's hoping he can do something similar this week for his current client, Uzbekistan blogger Otabek Sattoriy, who is currently serving a six-and-half-year prison sentence on convictions of defamation and extortion. Davlatov says the case against his client was manufactured in retaliation for Sattoriy's aggressive reporting about corruption at the state-run gas company and his repeated criticism of local officials near Termez, on the border of Uzbekistan and Afghanistan. On March 30, Sattoriy's case is scheduled to appear before the three judge Supreme Court in Tashkent. The crimes alleged against Sattoriy seem small and hardly warranting such a long prison sentence. In December 2020, Sattoriy was filming a farmers' market when guards scuffled with him and broke his phone. Apparently he demanded his phone, valued at $436, be replaced. After he received a new phone he was charged with extortion. Additional charges of extortion and defamation were added when other people stepped forward claiming Sattoriy tried to blackmail them, too, unless they paid him. One of the charges involved Sattoriy asking that his parents be compensated after the government allowed a construction company to demolish their home to make way for an apartment building, a common problem in Uzbekistan. "All these arrests are due to his journalist activities," Davlatov insisted. "They are trying to stop too many journalists." He named four other bloggers who were detained by the government last week. Bloggers in this country are not considered or treated like journalists. They are not licensed or registered like official journalists. And often they take money to write about problems. "It's just a scheme to make money. It's a business," I heard one journalist and after another say. Many journalists here disdain bloggers, and nearly every journalist I have interviewed in this country believes Sattoriy is not innocent. "We investigated the Ottabek Sattoriy case," Abdukadirov Dilshod, editor in chief at Kun.uz, told me. Kun.uz is one of the more popular independent news sites in Tashkent and the outlet has faced its own battles with the government. In 2018, the government blocked their site for a week and fined them for writing about religious material without having the government's approval. But Kun.uz is not sympathetic to the plight of Sattoriy. "Sattoriy is guilty of violating the law," Dilshod said. "This is not a freedom of speech case and we are not taking his side." I heard similar accusations from other editors in Tashkent. Even Davlatov isn't crazy about the common practices of bloggers. "Bloggers will say anything. Sometimes they are not ethical. They don’t know ethics or the ethics of journalism. They made this a business and are not objective. They want to become Internet stars." Davlatov is a blogger himself. He shows me his Youtube channel. "I believe in journalism and in fighting corruption," he says. "If I know someone is innocent then I invite them to my own channel to be interviewed." Perhaps Davlatov will have a chance to invite his client Sattoriy after the Supreme Court hearing next week. Feruza Najmiddinova, deputy editor at Qalampir in Tashkent, stands before one of the walls at the news outlet dedicated to Uzbek domestic violence victims. She was the target of a sex video last year. On Friday I interviewed a young female journalist who seven months ago was threatened with a widely circulated sex video on social media. The video showed a woman having sex on a balcony with a man and claimed the woman was Feruza Najmiddinova, then a 29-year-old journalist working for the Qalampir news outlet in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Feruza had just published an article critical of restaurants in a business complex owned by the Mayor of Tashkent that were regularly breaking the 8 p.m. curfew during the city's Covid quarantine but were not fined by police.

Feruza is a married Muslim woman. This tactic of publicizing sex videotapes is popular in other Muslim countries, such as Azerbaijan, where Khadija Ismayilova, an investigative journalist, was also the target of such a video ten years ago. (See my story about Khadija in the Post.) In 2012, a blackmail video of Khadija having sex with her then-boyfriend surfaced on pro-government websites. Muslim women have been killed for shaming their families by having sex before marriage or with men who are not their husbands. When a close family member learned of the videotape, he was so angry at Khadija, he brought a knife to confront her. In Feruza's case, she was not the woman in the video, but the attempt to shame her publicly and pressure her to stop reporting on controversial subjects was still the intent of those who posted the video. Only in this case, that blackmail backfired. Instead of humiliating her, the video enraged the public. Many organizations, including several governmental bodies and other media organizations, came out and supported the journalist. Harassment on the Internet "remains one of the most disgusting ways to put pressure on journalists," Kamil Allamjanov, an Uzbekistan media ombudsmen told reporters at the time. "The more horrible a lie, the easier it is to believe it," he said. "The goal is to intimidate journalists and force them to resign." Even the President of Uzbekistan's daughter, Saida Mirziyoyeva, created a video message addressed to female journalists urging them not to give in to such blackmail. She ended her social media post with #IamFeruza. That hashtag went viral. Many other women and men began using it to show support for Feruza and female journalists. The outpouring of support forced the police to open an investigation into who made and distributed the the video, but so far nothing has been discovered. Feruza told me she never considered quitting her job as a journalist when the video came out, but her family fears that this kind of harassment and intimidation will end up hurting other family members and possibly Feruza's future children. Her husband, she said, worries about her and even before this incident warned her not to get into conflicts in her reporting. Her editor at Qalampir, Kamariddin Shaykhov, said he and other editors always feared that something like this might happen to one of their journalists. He never anticipated such widespread support, though. He fears that the next time someone tries to blackmail a journalist, the outrage might not be so vocal or widespread. Now whenever Feruza reports a story with conflict, the sex video weighs heavily on her mind, and she fears for her family. Seven months later she is still experiencing occasional intimidation on stories. Sometimes people post comments online, "Wasn't it better to be on the balcony?" or warning her: "Remember the balcony." The Feruza video scandal has had a chilling effect on other female journalists in Uzbekistan. One female journalist told me that whenever she is covering controversial stories, she's had subjects warn her, "Be careful, you don't want to become another Feruza." We arrived here at 2 a.m. on Thursday morning, still Wednesday in the U.S. The airport was like most post-Soviet airports— long passports lines for foreigners, unguarded baggage claim, hoards of taxi drivers all yelling at us as we parted through them with our four giant pieces of luggage, two small bags, and two backpacks. I could have been arriving in Kyiv's Boryspil airport or the train station. The scene was so similar. Tashkent is a city of smaller buildings than Kyiv, though those buildings look the same, concrete monstrosities. Inside, though they are sleek and modern, a tribute to the craftsman in post-Soviet countries.

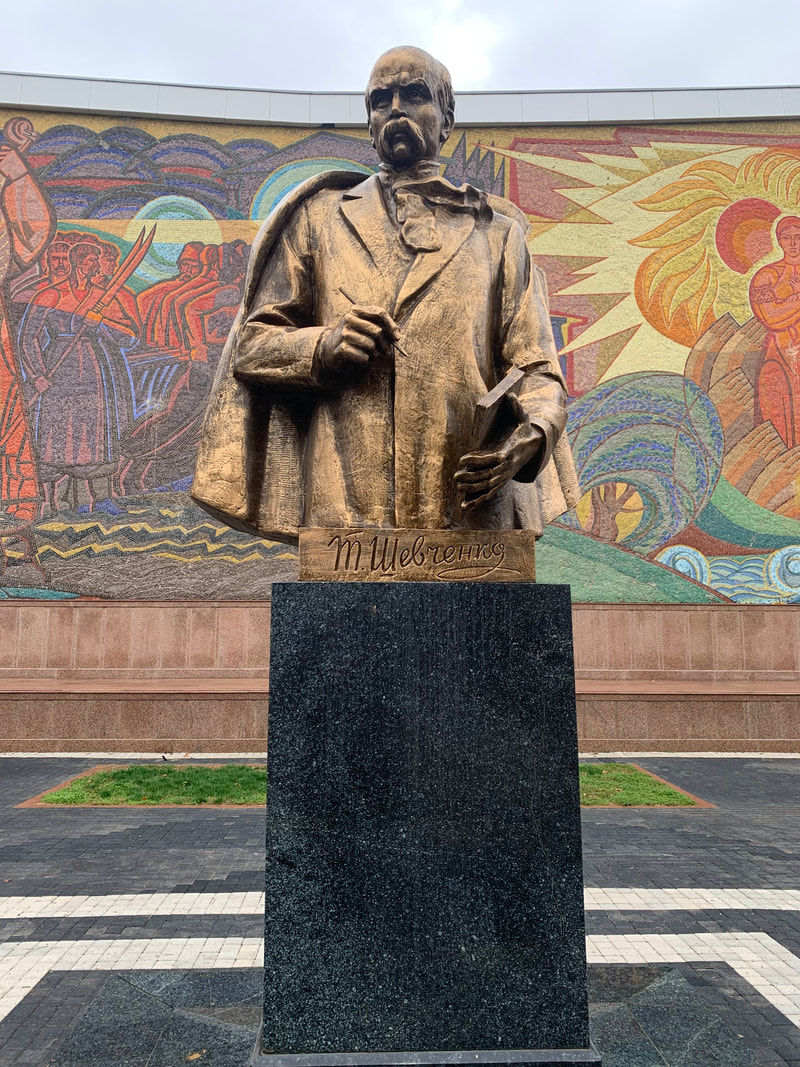

As soon as we arrived, we learned we were not the only immigrants to discover Uzbekistan, a sleepy small country on the edge of the old Soviet maps. Russian and Belorussian bloggers and programmers and businessmen who couldn't function in their countries fled to Uzbekistan, which has officially declared that it is Switzerland in the fight between Ukraine and Russia. Some fight. More and more Ukrainians are dying and every day I worry about my former students, our friends and former neighbors. So, we have had to do strong negotiations to get anyone to rent us an apartment for 2.5 months. "Why should I rent to you," one landlord said, "when I can rent to Belorussians for twice the amount?" It turns out everyone is a capitalist. As we were walking around our new neighborhood, I found this statue of Taras Shevchenko, a Ukrainian poet, in front of a beautiful Soviet mosaic. Why is this Ukrainian poet being honored in Uzbekistan, hundreds of miles from his homeland? There are so many reminders of Ukraine here because post-Soviet countries still have the same culture. No one likes to admit it, but it's true. For example, the whole bureaucratic rental system is the same here as it is in Ukraine. We moved into an apartment over the weekend and had to wait until Monday (today) to register. Literally every foreigner must register with the Uzbek government every single day or face a fine of $2,000 a day. Ouch! You must register to rent an apartment and then the lease must be registered with the government tax office. Every person along the way has their hand out. We were told that my host agency, called The Agency, which has a long name which basically means they are the government censors, must write us a letter. But the US Embassy told us we didn't need such a letter. But the government registrars demanded we produce a letter. Much negotiations. The US Embassy made phone calls. The landlord demanded we pay him three months rent. The real estate agents demanded we pay them their fee. Or else we were on the street with our bags (did I mention how many of them there are and that we had to hire a cargo truck to move them to the apartment?) and the raw chicken and mutton I bought at the grocery store. I could see us standing in the rain —it has rained here for a solid week—holding the smelly meat and our bags. Oh my god. My husband was furious as everyone was demanding money. He stood up—he is a tall man and even taller in a country of short people—and said, "We have to leave this country. They are trying to kick us out!" But the traveling gods smiled on us and delivered an amazing English speaking Kazakh who negotiated for us. So we have a place to stay for a few days. Stay tuned. Today my husband and I secured our Kazakhstan visas. Last week, Uzbekistan finally granted us visas after several weeks of negotiations. And so tomorrow, after a year and half of waiting, Greg and I will begin my Fulbright to Central Asia. The first leg begins in Uzbekistan. After two calendar days of flying, we'll finally land in Tashkent at 2 a.m.

|

Fulbright in Central AsiaFrom March, 2022 to January of 2023, I was a Fulbright Scholar with the U.S. State Department in post-Soviet Central Asia. My previous Fulbright was in Ukraine. For the past six years, I have reported on journalists from post-Soviet countries who have experienced retaliation for reporting the truth. Archives

January 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed