The Most Notorious Towing Company in Chicago—Maybe in America—Gets the Boot

The ‘Lincoln Park Pirates’ hauled off cars for no reason, Windy City residents long contended; ‘They tormented people for years. For years!’

By

Douglas Belkin

Sept. 13, 2018 3:09 p.m. ET

CHICAGO—In a city known for gangsters, bootleggers and corrupt politicians, residents will tell you the most reviled actor on the North Side is a tow-truck company.

For more than half a century, Chicagoans have said Lincoln Towing Service—locally known as the Lincoln Park Pirates—has hauled away cars for no reason, overcharged motorists to get them back and taunted owners who complained.

Douglas Belkin

Sept. 13, 2018 3:09 p.m. ET

CHICAGO—In a city known for gangsters, bootleggers and corrupt politicians, residents will tell you the most reviled actor on the North Side is a tow-truck company.

For more than half a century, Chicagoans have said Lincoln Towing Service—locally known as the Lincoln Park Pirates—has hauled away cars for no reason, overcharged motorists to get them back and taunted owners who complained.

A frightful sight in Chicago

One woman spent two years in court pursing a complaint after she said Lincoln towed her car from her leased space one winter when she was pregnant, and accused her of being a drunk. A child-protection investigator said after Lincoln towed his car, employees at its lot laughed at him when he pointed out he had been on official business at a police station.

On Wednesday, a state commission revoked Lincoln’s commercial vehicle relocators license. Chicago cheered. Twitter bubbled with schadenfreude.

“Oh, man that’s great news!” said Andrew Bani, a cabdriver from Nigeria who said Lincoln towed him four or five times over the years. “I’m happy, I’m happy, I’m happy. I don’t know if it’s karma or what, but they tormented people for years. For years!”

A person reached by phone at Lincoln said the company had no comment. Employees at Lincoln’s yard directed inquiries to Allen Perl, the company’s lawyer, who didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Mr. Perl told the local ABC News affiliate that Lincoln will fight the decision and that there was no evidence at the hearing to show it was guilty of unauthorized towing, adding: “It’s our position that we will be allowed to remain open during the appeal process.”

One woman spent two years in court pursing a complaint after she said Lincoln towed her car from her leased space one winter when she was pregnant, and accused her of being a drunk. A child-protection investigator said after Lincoln towed his car, employees at its lot laughed at him when he pointed out he had been on official business at a police station.

On Wednesday, a state commission revoked Lincoln’s commercial vehicle relocators license. Chicago cheered. Twitter bubbled with schadenfreude.

“Oh, man that’s great news!” said Andrew Bani, a cabdriver from Nigeria who said Lincoln towed him four or five times over the years. “I’m happy, I’m happy, I’m happy. I don’t know if it’s karma or what, but they tormented people for years. For years!”

A person reached by phone at Lincoln said the company had no comment. Employees at Lincoln’s yard directed inquiries to Allen Perl, the company’s lawyer, who didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Mr. Perl told the local ABC News affiliate that Lincoln will fight the decision and that there was no evidence at the hearing to show it was guilty of unauthorized towing, adding: “It’s our position that we will be allowed to remain open during the appeal process.”

The company’s website says “Lincoln Park Towing has NEW MANAGEMENT with a BETTER understanding of ALL your parking needs.”

The Illinois Commerce Commission, which issues tow licenses, said Wednesday it determined that Lincoln “has not conducted its business with honesty and integrity, that it is—in fact—incompetent or unworthy to be entitled to hold a Commercial Vehicle Relocators License.”

“Good for them!” said Patrick Armstrong, an investigator with the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services, speaking of the commerce commission after hearing it yanked Lincoln’s license.

Mr. Armstrong said he parked his car across from a police station where he was discussing a child-abuse case in 2015, when Lincoln towed it despite his valid parking placard. He and a sergeant went to Lincoln’s office, he said, where an employee laughed at their complaint. He paid several hundred dollars to get his car back.

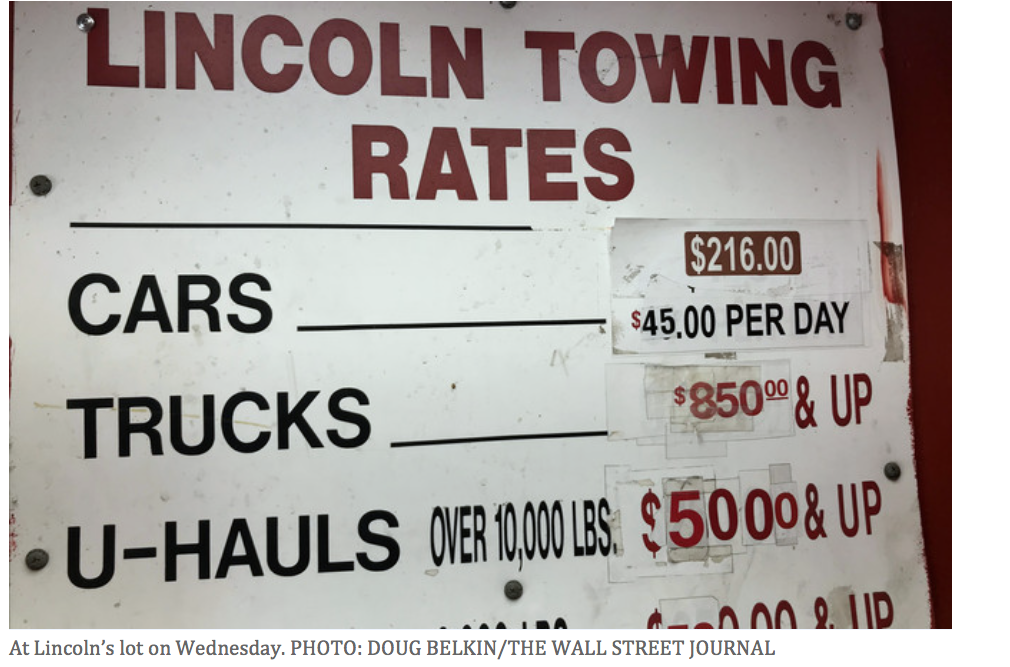

Last year, Cheryl Reed was at a launch party for her new novel, she said, when Lincoln illegally hauled her car from a lot. When she called the company, the person hung up, she said. When she went to the lot tell them there was a mistake, she said, employees laughed at her. A journalism professor at Syracuse University, she challenged the $218 ticket and eventually got a refund.

The Illinois Commerce Commission, which issues tow licenses, said Wednesday it determined that Lincoln “has not conducted its business with honesty and integrity, that it is—in fact—incompetent or unworthy to be entitled to hold a Commercial Vehicle Relocators License.”

“Good for them!” said Patrick Armstrong, an investigator with the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services, speaking of the commerce commission after hearing it yanked Lincoln’s license.

Mr. Armstrong said he parked his car across from a police station where he was discussing a child-abuse case in 2015, when Lincoln towed it despite his valid parking placard. He and a sergeant went to Lincoln’s office, he said, where an employee laughed at their complaint. He paid several hundred dollars to get his car back.

Last year, Cheryl Reed was at a launch party for her new novel, she said, when Lincoln illegally hauled her car from a lot. When she called the company, the person hung up, she said. When she went to the lot tell them there was a mistake, she said, employees laughed at her. A journalism professor at Syracuse University, she challenged the $218 ticket and eventually got a refund.

“They were like little mobsters, ‘We tow your car, you have to pay,’ they could care less if the car was parked legally,” she said. “They were really mean and nasty and there is no reason why those people should be in business.”

A commerce-commission report found that between July 2015 and March 2016, Lincoln towed 9,470 vehicles. Of those, more than 800 were unauthorized—cars towed by unlicensed drivers, for example, or relocated without a property owner’s consent or towed from lots where other companies had contracts.

In 1972, Chicago folk singer Steve Goodman—he wrote “City of New Orleans” and, importantly, “Go Cubs Go”—wrote the song “Lincoln Park Pirates” about the tow service. The name stuck.

The song goes, in part:

All my drivers are friendly and courteous,

Their good manners ya always will get,

’Cause they’re all recent graduates of the charm school in Joliet [translation: Joliet Prison].

Mr. Goodman’s song on YouTube.

In one of his many columns about the towing service, Chicago’s late, great newspaper columnist Mike Royko called Ross Cascio, the late founder, “a hulk of a man who liked to sit in his caged office, counting bullets and threatening to unleash his red-eyed, black-tongued dog on those who dared refuse to ransom their cars.”

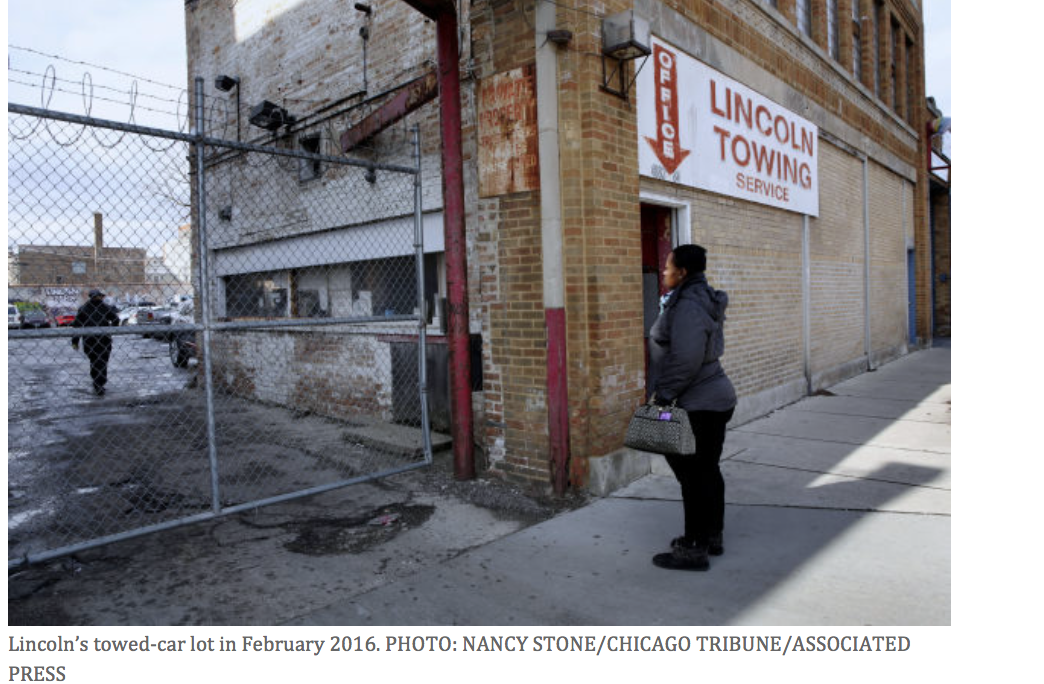

At Lincoln’s tow yard, across from a cemetery, a chain-link fence topped with barbed wire blocks the driveway. By the rusty-red office door, a sign reads: “Vehicles left over 5 days will be taken to our storage lot.”

In the corner is scratched: “hells graveyard.”

A sign at Lincoln’s lot. PHOTO: DOUG BELKIN/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Metal bars stand between owners and employees holding their vehicles. On Wednesday, a man behind those bars, identifying himself as a tow-truck driver there for 20 years, said the only bad attitudes came from people standing on the other side of the bars.

“Why would we ever yell at anyone?” he said. “If they don’t park where they’re not supposed to, they won’t get towed,” he said.

When Abby Amey walked into that alcove in 2014, she said, she was six months pregnant and the windchill was minus 40. Lincoln had towed her car from a space she leased, she said. After she presented her lease, she said the man behind the bars yelled: “You’re a drunk!”

She spent two years pursuing the case and won $2,000 in damages in civil court, she said. “I refused to let it go.”

Few drivers went that far, said Alderman Ameya Pawar, who fought to successfully pass a Chicago Towing Bill of Rights. “If you get your car towed for nothing you’re really angry,” he said, “but you have to get on with your life.”

Shortly after Ms. Amey’s experience, Lincoln towed a car whose owner was out of the country, said the owner’s son-in-law, Josh Thalheimer. The owner used Google Earth images to show it was usually parked in a legal spot and shouldn’t have been towed, he said. The family took the story to the media. Lincoln returned the car at no cost, he said, with a damaged mirror.

“I thought, how many other people has this happened to?” said Basil Diab, a Chicago financial-services professional who, after reading of the case, started a petition in 2016 asking for an investigation of Lincoln.

It garnered 3,500 signatures.

When Mr. Pawar heard the verdict, he said, he had one thought.

“Finally!”

Write to Douglas Belkin at [email protected]

A commerce-commission report found that between July 2015 and March 2016, Lincoln towed 9,470 vehicles. Of those, more than 800 were unauthorized—cars towed by unlicensed drivers, for example, or relocated without a property owner’s consent or towed from lots where other companies had contracts.

In 1972, Chicago folk singer Steve Goodman—he wrote “City of New Orleans” and, importantly, “Go Cubs Go”—wrote the song “Lincoln Park Pirates” about the tow service. The name stuck.

The song goes, in part:

All my drivers are friendly and courteous,

Their good manners ya always will get,

’Cause they’re all recent graduates of the charm school in Joliet [translation: Joliet Prison].

Mr. Goodman’s song on YouTube.

In one of his many columns about the towing service, Chicago’s late, great newspaper columnist Mike Royko called Ross Cascio, the late founder, “a hulk of a man who liked to sit in his caged office, counting bullets and threatening to unleash his red-eyed, black-tongued dog on those who dared refuse to ransom their cars.”

At Lincoln’s tow yard, across from a cemetery, a chain-link fence topped with barbed wire blocks the driveway. By the rusty-red office door, a sign reads: “Vehicles left over 5 days will be taken to our storage lot.”

In the corner is scratched: “hells graveyard.”

A sign at Lincoln’s lot. PHOTO: DOUG BELKIN/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Metal bars stand between owners and employees holding their vehicles. On Wednesday, a man behind those bars, identifying himself as a tow-truck driver there for 20 years, said the only bad attitudes came from people standing on the other side of the bars.

“Why would we ever yell at anyone?” he said. “If they don’t park where they’re not supposed to, they won’t get towed,” he said.

When Abby Amey walked into that alcove in 2014, she said, she was six months pregnant and the windchill was minus 40. Lincoln had towed her car from a space she leased, she said. After she presented her lease, she said the man behind the bars yelled: “You’re a drunk!”

She spent two years pursuing the case and won $2,000 in damages in civil court, she said. “I refused to let it go.”

Few drivers went that far, said Alderman Ameya Pawar, who fought to successfully pass a Chicago Towing Bill of Rights. “If you get your car towed for nothing you’re really angry,” he said, “but you have to get on with your life.”

Shortly after Ms. Amey’s experience, Lincoln towed a car whose owner was out of the country, said the owner’s son-in-law, Josh Thalheimer. The owner used Google Earth images to show it was usually parked in a legal spot and shouldn’t have been towed, he said. The family took the story to the media. Lincoln returned the car at no cost, he said, with a damaged mirror.

“I thought, how many other people has this happened to?” said Basil Diab, a Chicago financial-services professional who, after reading of the case, started a petition in 2016 asking for an investigation of Lincoln.

It garnered 3,500 signatures.

When Mr. Pawar heard the verdict, he said, he had one thought.

“Finally!”

Write to Douglas Belkin at [email protected]