|

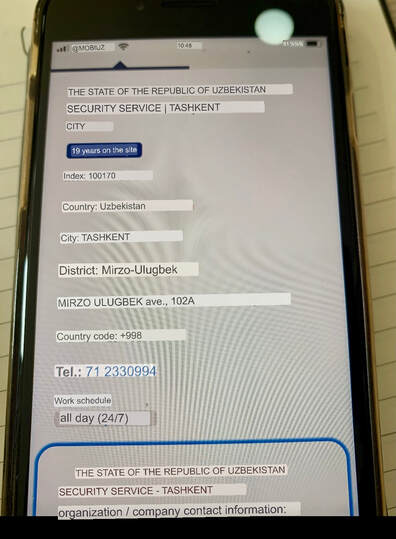

My quest to secure an interview with the State Security Services (SSS) in Uzbekistan is a story of the hunted becoming the hunter. One of my favorite Soviet era paintings from the Savistky collection of avant-garde art in Nukus, Uzbekistan is the 1971 "Hunter" by N.M. Nedbaylo, a Ukrainian. As a U.S. Fulbright Scholar researching the media in Uzbekistan, I have interviewed nearly 35 journalists, bloggers and media monitors. Nearly all of them say the No. 1 threat to reporting the truth in this country is the State Security Services (SSS). They claim the SSS, or what some call the “secret police,” routinely threaten harm to their families if they don’t delete stories and stop covering certain topics, like government corruption.  Just the idea of having to deal with the SSS elicits so much fear and trepidation that journalists self-censor and don’t even try to report stories that people here need to know. I have found journalists in Uzbekistan much more timid than other post-Soviet countries where the media laws are far more restrictive. When I asked why this was the case, Tashanov Abdurakhmon, chairman of the Ezgulik, Uzbekistan’s human rights agency told me: “When the government becomes more a bully, the people become more slaves. When the treatment becomes more harsh and more severe, the people become more timid and more abiding of authority, like North Korea.” One of the tenets of sound journalism is hearing what the other side has to say. It’s called being fair and balanced. With that in mind, I’ve been trying to talk with the SSS for a couple of weeks about these allegations of threats and intimidations. But the SSS is ignoring me. I feel like Michael Moore in his famous movie Roger & Me in which he tries to get an interview with General Motor’s Chairman Roger Smith. He follows him around the country, stakes out places Smith will be, but he can never get an interview. My host during my 2.5 month stay in Uzbekistan is The Agency for Information and Mass Communication, a government media monitoring agency, which one would think would easily be able to help me set up an interview with the SSS, another kind of monitoring agency. Tukhtasin Ghaybullayev is my contact there. On May 9, more than 10 days ago, I started asking him for help. Ghaybullayev finally told me I’d need to ask the U.S. Embassy to write a letter on my behalf to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. When I asked the Embassy if they could write such a letter, they said they’d never been asked to write a letter verifying the identity of an independent journalist and didn’t want to start such a precedent. I agreed. Why should the U.S. Embassy get involved with securing interviews for journalists? I don’t work for the U.S. government. I sent Ghaybullayev a copy of my international press credentials and insisted that these should be good enough. But he wouldn’t budge. Then I turned to Komil Allamjonov, head of Public Foundation for Support and Development of the National Mass Media, and asked if he could help me. “No one has actually asked me before to help them get an interview with the secret service,” Allamjonov said. “It’s a secret service. It’s name is 'secret service' you know,” he said laughing. "What they do is secret." Allamjonov said my contact at The Agency should contact the SSS’s press agent. But Ghaybullayev insisted he had no way to contact anyone at the SSS. I found this to be incredulous, particularly since The Agency had made a big deal to me that the government had installed press agents at all government organizations, and those agents were ordered to respond to requests within 24 hours. Surely they would know how to make contact. But my texts to Ghaybullayev went unanswered. So I thought maybe I could contact the SSS directly. I asked journalists who had frequently been contacted by the SSS if they could reach out and ask how I could secure an interview. “Why do you want to interview them?” One journalist after another asked. They all thought my request unusual. A few said they sent notes to people at the SSS, but no one heard back. One journalist told me I needed to write an article that would draw the SSS’s attention. So that’s what I’m doing. When I wrote an article about the SSS for Qalampir, the editor told me he couldn’t print a story that mentioned the SSS. So maybe the fact that I’ve been writing SSS many times in this piece will get their attention. One person jokingly told me the SSS doesn’t come out during the day. “They are like vampires,” he said. “They don’t like the light. They thrive in the dark.” Despite his admonition, he did give me a phone number that he found listed online for the SSS (see above photo, translated by Google Translate.) “No one ever answers,” he warned. I dialed the number. After two rings, a recording picked up. It was of a man’s voice telling me in English that the person couldn’t come to the phone and to call back later. I tried several times, over several different days. It was always the same recording. But why was it in English since I was dialing an Uzbekistan number from an Uzbekistan number? So back to The Agency. This time I just showed up at their offices. Maybe Ghaybullayev would stop ignoring me if I planted myself and refused to leave. You know, something like a sit-in protest. After several minutes of sitting in the Agency offices, Ghaybullayev showed up with another Agency official who spoke English and could translate. (Why would the Agency pair me with a guy who couldn’t speak English?) Ghaybullayev stuck to his line. The Embassy had to write a letter. That was the only way. Finally, when he saw I wasn’t going to leave, he suggested I write my own letter. And so I did. I emailed that letter to Norov Vladimir Imamovich, Uzbekistan’s Acting Minister of Foreign Affairs. Still no word. Then yesterday I had an interview with the head of the journalists union, Olimjon Usarov. He asked me why I hadn’t interviewed the SSS since so many of my findings involved that government agency. I detailed my quest and how I’d been asking for the interview for nearly two weeks. Usarov said he would try to help me. I’m still waiting. Hello Mr. SSS, are you listening? Meet Katerina Andreeva, one of the bravest journalists in all of the post-Soviet autocracies. Currently, Andreeva and her colleague, videographer Daria Chultsova, are serving the final six months of a two-year sentence in a prison colony for live-streaming a protest in Minsk in November of 2020. Because of the ludicrous nature of the charges and the "investigation," Andreeva defiantly asked the judge after hearing the verdict: “Why didn’t you give us 25 years?”

But last month, the Belarusian government handed down another charge against Andreeva. This time the charge is for treason and she now faces a prison sentence of 7 to 15 years. It's believed these charges are in relation to stories she reported about Belarusian soldiers for hire who fought in Donbas in Ukraine. The KGB conducted the investigation into these mysterious treason charges, Andreeva's husband, journalist Igor Ilyash, told me. He said the court will be closed and lawyers are not even allowed to tell him or Andreeva's family members the circumstances surrounding the charges. He's not even sure when the court will hear the case. I met Andreeva in the summer of 2018 while working on a story about retaliations against journalists in Belarus. The story was later published in the Washington Post. Then 24, Andreeva had already been detained twice by the police. Once she was strip-searched and falsely accused of hiding a camera in a crevice of her body. She showed me the stories about the Belarusian soldiers fighting in Donbas. Andreeva started reporting these stories back in 2017. So it seems strange that only now the government is coming after her for these reports. Or is it to send a message to other reporters not to report about Belarus's involvement in Russian's war in Ukraine? “The most dangerous thing you can do in Belarus is investigative reporting,” Andreeva told me then. But she refused to back down. Even as we spoke, a KGB officer was sitting across from us at a restaurant. His table spare, the guy wasn't even trying to hide the fact he was spying on us. Andreeva said he'd been following us since we left her apartment. She was used to such harassment by then. "I'm ready to go to prison if I have to," she told me. After our hours-long conversation, I told my husband that the Belarusian government would likely try to quash such defiance and determination. I've been thinking of Andreeva a lot these days. I've spent the last seven weeks in Uzbekistan interviewing journalists and bloggers here. In contrast to Belarus which has 19 journalists in prison, there are no journalists in prison here. But the fear and intimidation expressed by Uzbekistani journalists is palpable. Most are afraid to say anything that might draw attention to themselves. A few brave ones are defiant and tired of self-censoring. Most simply comply with government censors and then lie about it to the public—making up stories for why their website was off line for days or why their coverage of the war in Ukraine has suddenly gone from neutral to nothing but Russian propaganda. When I complain about such cowardice, I'm told that I must understand that these journalists have families and these editors have employees and they are just trying to protect them. But why even be a journalist if you don't have the stomach to face intimidation and harassment? When journalists excuse other journalists' passivity here, I think of Andreeva, who at 28 is facing 15 years in prison. If that happens, her youth and any chance of a family will be taken from her. I think of the other 18 journalists in prison in Belarus, the 24 journalists in prison in Russia, the 26 journalists in prison in Turkey and the three journalists who are in prison in Azerbaijan. The first rule of journalism is: Question authority. Unfortunately, not much of that is happening in Uzbekistan. |

Fulbright in Central AsiaFrom March, 2022 to January of 2023, I was a Fulbright Scholar with the U.S. State Department in post-Soviet Central Asia. My previous Fulbright was in Ukraine. For the past six years, I have reported on journalists from post-Soviet countries who have experienced retaliation for reporting the truth. Archives

January 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed