|

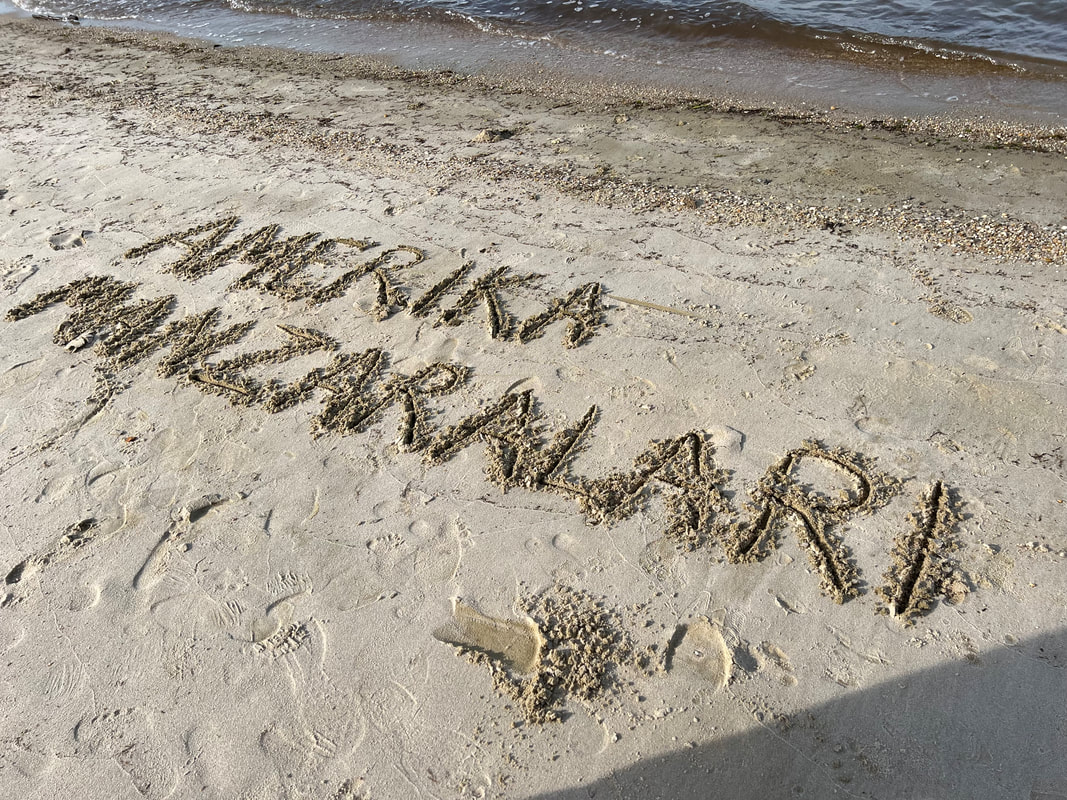

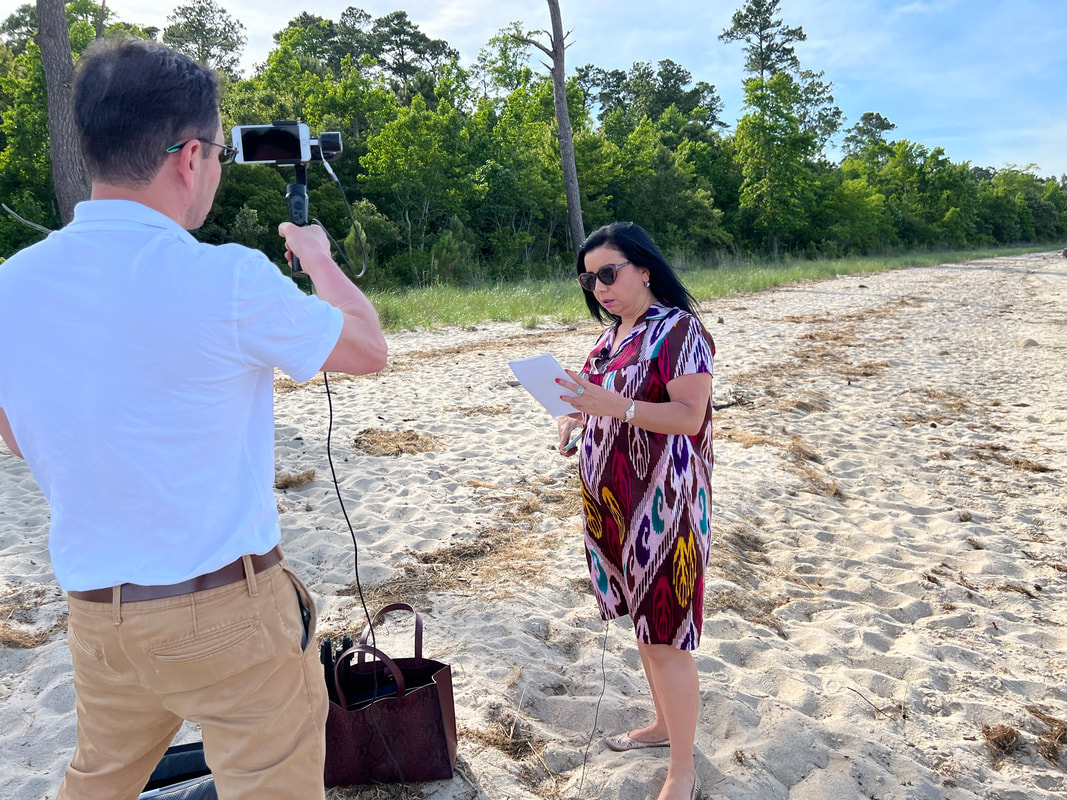

It was a day on the Chesapeake Bay. Navbahor Imamova and her film crew from Voice of America came to Northumberland County, Virginia, population 12,000, to spend the day recording an interview with me and taping Imamova's weekly news roundup. The result is an in-depth interview that takes viewers through my home, onto my dock and to the nearby beach at Hughlett's Point, a protected beach along the Chesapeake Bay.

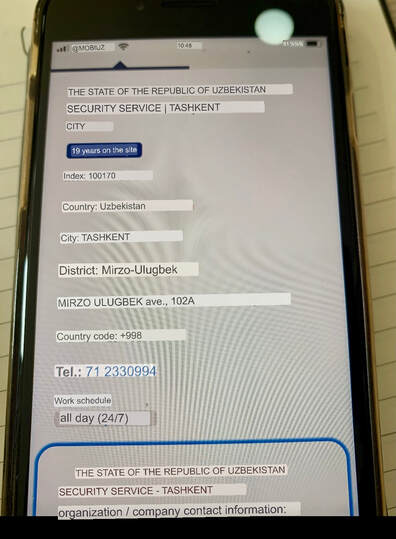

Imamova and I first met in Tashkent, Uzbekistan in mid-March, shortly after I'd arrived as a Fulbright Scholar. We spent three hours talking that first time and then went on to engage in multiple Telegram chats. Imamova is a wealth of information. She started her journalism career in Uzbekistan, and for the past twenty years has covered Central Asia for Voice of America. From the time I landed in Tashkent, I continued to hear from journalists and people at the U.S. Embassy that I absolutely had to talk to Imamova. And when I did, I understood why so many people inside Uzbekistan and out think so highly of her. That first chat, we had so much to talk about. I was in Uzbekistan to interview Uzbekistani journalists and determine what were the biggest challenges. Imamova offered her expertise and connected me with many journalists. I am deeply in debt to her for her assistance. Anyone paying attention to these pages knows that I found some very disturbing patterns with State Security Services (SSS) threatening, intimidating and forcing journalists to delete stories. Check out the interview here. Even if you just watch the film with the sound down, the video captures the beautiful landscape of coastal Virginia. Imamova and her team did an amazing job. My quest to secure an interview with the State Security Services (SSS) in Uzbekistan is a story of the hunted becoming the hunter. One of my favorite Soviet era paintings from the Savistky collection of avant-garde art in Nukus, Uzbekistan is the 1971 "Hunter" by N.M. Nedbaylo, a Ukrainian. As a U.S. Fulbright Scholar researching the media in Uzbekistan, I have interviewed nearly 35 journalists, bloggers and media monitors. Nearly all of them say the No. 1 threat to reporting the truth in this country is the State Security Services (SSS). They claim the SSS, or what some call the “secret police,” routinely threaten harm to their families if they don’t delete stories and stop covering certain topics, like government corruption.  Just the idea of having to deal with the SSS elicits so much fear and trepidation that journalists self-censor and don’t even try to report stories that people here need to know. I have found journalists in Uzbekistan much more timid than other post-Soviet countries where the media laws are far more restrictive. When I asked why this was the case, Tashanov Abdurakhmon, chairman of the Ezgulik, Uzbekistan’s human rights agency told me: “When the government becomes more a bully, the people become more slaves. When the treatment becomes more harsh and more severe, the people become more timid and more abiding of authority, like North Korea.” One of the tenets of sound journalism is hearing what the other side has to say. It’s called being fair and balanced. With that in mind, I’ve been trying to talk with the SSS for a couple of weeks about these allegations of threats and intimidations. But the SSS is ignoring me. I feel like Michael Moore in his famous movie Roger & Me in which he tries to get an interview with General Motor’s Chairman Roger Smith. He follows him around the country, stakes out places Smith will be, but he can never get an interview. My host during my 2.5 month stay in Uzbekistan is The Agency for Information and Mass Communication, a government media monitoring agency, which one would think would easily be able to help me set up an interview with the SSS, another kind of monitoring agency. Tukhtasin Ghaybullayev is my contact there. On May 9, more than 10 days ago, I started asking him for help. Ghaybullayev finally told me I’d need to ask the U.S. Embassy to write a letter on my behalf to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. When I asked the Embassy if they could write such a letter, they said they’d never been asked to write a letter verifying the identity of an independent journalist and didn’t want to start such a precedent. I agreed. Why should the U.S. Embassy get involved with securing interviews for journalists? I don’t work for the U.S. government. I sent Ghaybullayev a copy of my international press credentials and insisted that these should be good enough. But he wouldn’t budge. Then I turned to Komil Allamjonov, head of Public Foundation for Support and Development of the National Mass Media, and asked if he could help me. “No one has actually asked me before to help them get an interview with the secret service,” Allamjonov said. “It’s a secret service. It’s name is 'secret service' you know,” he said laughing. "What they do is secret." Allamjonov said my contact at The Agency should contact the SSS’s press agent. But Ghaybullayev insisted he had no way to contact anyone at the SSS. I found this to be incredulous, particularly since The Agency had made a big deal to me that the government had installed press agents at all government organizations, and those agents were ordered to respond to requests within 24 hours. Surely they would know how to make contact. But my texts to Ghaybullayev went unanswered. So I thought maybe I could contact the SSS directly. I asked journalists who had frequently been contacted by the SSS if they could reach out and ask how I could secure an interview. “Why do you want to interview them?” One journalist after another asked. They all thought my request unusual. A few said they sent notes to people at the SSS, but no one heard back. One journalist told me I needed to write an article that would draw the SSS’s attention. So that’s what I’m doing. When I wrote an article about the SSS for Qalampir, the editor told me he couldn’t print a story that mentioned the SSS. So maybe the fact that I’ve been writing SSS many times in this piece will get their attention. One person jokingly told me the SSS doesn’t come out during the day. “They are like vampires,” he said. “They don’t like the light. They thrive in the dark.” Despite his admonition, he did give me a phone number that he found listed online for the SSS (see above photo, translated by Google Translate.) “No one ever answers,” he warned. I dialed the number. After two rings, a recording picked up. It was of a man’s voice telling me in English that the person couldn’t come to the phone and to call back later. I tried several times, over several different days. It was always the same recording. But why was it in English since I was dialing an Uzbekistan number from an Uzbekistan number? So back to The Agency. This time I just showed up at their offices. Maybe Ghaybullayev would stop ignoring me if I planted myself and refused to leave. You know, something like a sit-in protest. After several minutes of sitting in the Agency offices, Ghaybullayev showed up with another Agency official who spoke English and could translate. (Why would the Agency pair me with a guy who couldn’t speak English?) Ghaybullayev stuck to his line. The Embassy had to write a letter. That was the only way. Finally, when he saw I wasn’t going to leave, he suggested I write my own letter. And so I did. I emailed that letter to Norov Vladimir Imamovich, Uzbekistan’s Acting Minister of Foreign Affairs. Still no word. Then yesterday I had an interview with the head of the journalists union, Olimjon Usarov. He asked me why I hadn’t interviewed the SSS since so many of my findings involved that government agency. I detailed my quest and how I’d been asking for the interview for nearly two weeks. Usarov said he would try to help me. I’m still waiting. Hello Mr. SSS, are you listening? Meet Katerina Andreeva, one of the bravest journalists in all of the post-Soviet autocracies. Currently, Andreeva and her colleague, videographer Daria Chultsova, are serving the final six months of a two-year sentence in a prison colony for live-streaming a protest in Minsk in November of 2020. Because of the ludicrous nature of the charges and the "investigation," Andreeva defiantly asked the judge after hearing the verdict: “Why didn’t you give us 25 years?”

But last month, the Belarusian government handed down another charge against Andreeva. This time the charge is for treason and she now faces a prison sentence of 7 to 15 years. It's believed these charges are in relation to stories she reported about Belarusian soldiers for hire who fought in Donbas in Ukraine. The KGB conducted the investigation into these mysterious treason charges, Andreeva's husband, journalist Igor Ilyash, told me. He said the court will be closed and lawyers are not even allowed to tell him or Andreeva's family members the circumstances surrounding the charges. He's not even sure when the court will hear the case. I met Andreeva in the summer of 2018 while working on a story about retaliations against journalists in Belarus. The story was later published in the Washington Post. Then 24, Andreeva had already been detained twice by the police. Once she was strip-searched and falsely accused of hiding a camera in a crevice of her body. She showed me the stories about the Belarusian soldiers fighting in Donbas. Andreeva started reporting these stories back in 2017. So it seems strange that only now the government is coming after her for these reports. Or is it to send a message to other reporters not to report about Belarus's involvement in Russian's war in Ukraine? “The most dangerous thing you can do in Belarus is investigative reporting,” Andreeva told me then. But she refused to back down. Even as we spoke, a KGB officer was sitting across from us at a restaurant. His table spare, the guy wasn't even trying to hide the fact he was spying on us. Andreeva said he'd been following us since we left her apartment. She was used to such harassment by then. "I'm ready to go to prison if I have to," she told me. After our hours-long conversation, I told my husband that the Belarusian government would likely try to quash such defiance and determination. I've been thinking of Andreeva a lot these days. I've spent the last seven weeks in Uzbekistan interviewing journalists and bloggers here. In contrast to Belarus which has 19 journalists in prison, there are no journalists in prison here. But the fear and intimidation expressed by Uzbekistani journalists is palpable. Most are afraid to say anything that might draw attention to themselves. A few brave ones are defiant and tired of self-censoring. Most simply comply with government censors and then lie about it to the public—making up stories for why their website was off line for days or why their coverage of the war in Ukraine has suddenly gone from neutral to nothing but Russian propaganda. When I complain about such cowardice, I'm told that I must understand that these journalists have families and these editors have employees and they are just trying to protect them. But why even be a journalist if you don't have the stomach to face intimidation and harassment? When journalists excuse other journalists' passivity here, I think of Andreeva, who at 28 is facing 15 years in prison. If that happens, her youth and any chance of a family will be taken from her. I think of the other 18 journalists in prison in Belarus, the 24 journalists in prison in Russia, the 26 journalists in prison in Turkey and the three journalists who are in prison in Azerbaijan. The first rule of journalism is: Question authority. Unfortunately, not much of that is happening in Uzbekistan. Dilfuza Ibodova runs a news website in Bukhara.  I am in Bukhara, sitting on a rooftop overlooking an amazing city of turquoise and lapis-colored madrassas and mausoleums. The architecture along the ancient Silk Road in Uzbekistan is amazing. And so are the stories. I've now conducted 38 interviews in Uzbekistan since arriving six weeks ago. These are hours-long conversations in which journalists and bloggers and sometimes human rights advocates detail specific threats and intimidations they and others have experienced. Just last week in Tashkent, Anora Sodikova from Rost 24 (photo left) announced she had to delete a video and an article about an Uzbekistan businessman who appeared in the Panama Papers, the huge database showing owners of offshore accounts. A "very powerful person" contacted a colleague of hers and told him if Anora wanted a "quiet life" she'd have to take down the article and video she posted on her website. Fearing for her family, Anora took down the report. But when she refused to take down her Facebook post that said she was in danger, a "sniper blogger" started a smear campaign about her. Anora told me the identity of this "very powerful person" but because she fears he will follow through on his threats I cannot tell you. That's the way it is in Uzbekistan. Everyone knows, but no one can say out loud. Journalists and bloggers are also afraid in the regions. I interviewed several journalists last week in Samarkand. A few of them were defiant and said they didn't care if officials threatened them. Others hemmed and hawed about whether I could tell their story on the record—and in the end they said yes. I've started a growing list of the brave journalists I've met here. At the top of that list is Dilfuza Ibodova, who runs the media website tezkor-yangiliklar.uz/. I was connected to Dilfuza through Tashanov Abdurakhmon, President of Ezgulik, Uzbekistan's official human rights agency. Tashanov called Dilfuza "an active and brave blogger." I didn't know much about her when we first met. (Sometimes it's hard to find information in English on news sites in this country.) For our first interview, Dilfuza and I met at the famous Lyabi House next to the giant fountains in Bukhara this week. Dilfuza brought her teenage daughter as a translator. Her daughter is studying English at the university. The poor girl struggled to keep up with the complex conversation. Even professional translators have problems translating such detailed conversations. Soon all three of us were typing furiously on our phones on Google translate. What was confusing to me is that Dilfuza said the SSS (or SNB or DXX or KGB, there are so many acronyms for the state security services here) didn't contact her. No one ever told her what to write, and she wrote about corruption of officials all the time. Judicial corruption and crime was in fact just about all she wrote. We continued this back and forth for awhile. She said she didn't feel fear and she felt she could write about anything she wanted as long as she provided documentation, also known as "proofs" here. Finally I asked Dilfuza: "Why is it that all these other journalists and bloggers are having trouble with the SSS and you are not?" Then she typed on her phone and held up the translation to me: "They don't bother me because they killed my brother in 2015." Stay-tuned. I'll soon detail more about this brave woman's story and those of others like her. Bahodirxon Eliboyev, a journalist-turn-blogger, and me in a ceramics factory in the Fergana Region of Uzbekistan. I am in Fergana, and I am being tracked. The State Security Services (SSS) contacts journalists after I have met with them. The SSS calls the hotel where I am staying several times a day and asks: Where has she gone? Who is she meeting with? What is the name of her translator? Other guests have even commented to me about these phone conversations. My interview subjects tell me they feel paranoid. Who informed on them? I tick through a small list of people who knew about my interviews. Who would inform on me? I sense a growing paranoia within me. It’s like I’m living in a Soviet time warp—or as one journalist told me—the Soviet Union 2.0. It’s not that I’m not used to such monitoring. Uzbekistan is the tenth post-Soviet country I’ve visited. But in places like Belarus, the KGB were more obvious. They sat across from me in restaurants, their tables spare and stared at me and whomever I was interviewing. Or they openly filmed me at public protests. I’m sure there’s a fat file in Minsk about me. Journalists in former Soviet states often know those who follow them. The security services there make it a point to be seen. Here the security forces’ secrecy feels much more menacing. “Pressure from the security services has only gotten worse over time,” explains Bahodirxon Eliboyev, a journalist turned blogger in Rishtan. Government spying and monitoring has had a chilling effect on both journalists and citizens, he said. His observations echo what journalists in Tashkent have told me. “Our journalism now is getting very dangerous,” Eliboyev said. “The security services can buy some journalists. If the authorities order, journalists write everything that officials want. That’s not journalism. That’s propaganda. Censorship is now in our minds and our hearts.” Unlike most journalists I’ve met in Uzbekistan, Eliboyev speaks openly about pressure journalists face. But he says normal citizens increasingly are afraid to speak out by name about wrongdoings they witness. “Citizens are afraid to talk to journalists because they can lose their jobs,” he said. “We have to teach them not to be afraid.’’ He says that filing stories with anonymous sources doesn’t carry the same authority as quoting people by name. “If I use anonymous names to protect them then it’s not developing journalism here. And I want to develop my country.” Eliboyev is controversial. He was fired from his first two jobs as a reporter after graduating with a journalism degree from Tashkent University. He then started two publications in Tashkent, but each time the prosecutor shut him down, he said. So he turned to human rights activism and blogging. On July 24, 2018, Eliboyev said he wrote a post on his blog wishing President Mirziyoyev a happy birthday and asking him not to forget the millions of Uzbek migrant workers who live in Russia and other countries because they can’t make a living in their home country. That afternoon four SSS officers pounded on the door of his garage apartment where he was napping. “When they saw I was living out of a garage, they asked; ‘Don’t you have a home?’ ” He said he told them: “I can’t work as a journalist. So where can I live? I can’t earn money at the one thing I’m good at.” They warned him he would go to jail if he kept writing about forbidden topics. He said he told them: “I can write whatever I want because your jail is like my garage. But your jail is more comfortable because I don’t need to find bread. You bring me bread. Your jail is for me freedom.” Eliboyev continues to blog about controversial topics. Just last week he says he was visited by the head of the terrorism police and told to delete a post or face a five-day detention and a 1.5 million sum fine. He deleted the post. Two hours after we met, Eliboyev sent me a text. He’d just gotten off the phone with the SSS. They wanted to know what he told me, he said.

“Censorship is inside of themselves,” he says. But self-censorship is real if a media outlet doesn’t want to lose licenses for crossing unknown red lines. At Ruxsor TV, near Fergana city, singer Nuriddin Asqarov says he pumped all his money into the television venture. I asked how the station had handled coverage of the Ukraine war. The general manager, Ibrohim Halimbekov, said the station is only licensed to produce 10 percent news. When I pressed further, I sensed employees in the room getting nervous. “We just cover life,” explained Halimbekov. “We do short reports on what is going on in the world. But we can’t go into detail. We are an entertainment station. We will lose our license.” Fear has forced some bloggers out of business. I met with former blogger Otabek Nuritdinov in his hometown Asaka in the Andijan region. In January 2020, Nuritdinov was detained for 15 days and fined over $1400 on charges of “slander, insult and disorderly conduct.” As Nuritdinov recounted these events, it was hard to imagine the soft-spoken man dressed in a blazer insulting anyone. After he was released, Nuritdinov faced more threats of arrest. In response, he refused to leave his house for six months. Shortly afterward he stopped blogging. At first Nuritdinov was hesitant to meet with me and to speak on the record. He doesn’t want any further problems with the government, he said. I went to Andijan and toured Nuritdinov’s tree nursery and, at his insistence, planted tree seedlings. After our three-hour interview, Nuritdinov agreed to let me use his name. But he asked me to be sure to mention his new venture of growing trees to produce clean air. Though he was still nervous when we parted, Nuritdinov posted pictures of us on his social media accounts. Everyone I met did this, even those who were nervous about being questioned by the SSS. I’m told that bloggers and journalists do this because there’s some cache in meeting with an American journalist. But I suspect there’s also an element of protection, that if they publicly acknowledge such interviews then they can’t be accused of meeting in secret.

She said she leads a clean life, doesn’t smoke or drink to eliminate any chance such vices can be used against her. Most importantly, she backs up her stories with documents, court papers and audio recordings. And she knows where the red lines are: she refrains from writing about the president or his family, religion, LGBT issues and private relationships between two people.

But even her precautions didn’t protect her from being questioned in 2016 by the SSS about why she was writing under pseudonyms in Ozodlik and the BBC. Then in 2020, Madrakhimov was shooting a video at a street market when a representative of the local governor grabbed her and took her to the police. She was detained for two hours while the police grilled her about why she was shooting the video. Finally, the governor called and told police that she was a journalist and to let her go. During last year’s presidential elections, she was asked not to report her observations until after the election, but she refused and posted stories anyway. After our interview, Madrakhimov texted me that the SSS had called her and asked what she was doing in Rishtan. She admitted she had met with me. (She also posted a picture of us on her Facebook account.) If they contact her again, she said, she will write about it in detail on Facebook. What troubles me about the SSS’s surveillance of me, is that my research of challenges faced by Uzbekistan journalists has been approved by the government. My official host is the Agency for Mass Media and Communication. So why did the security services in Fergana covertly track me? Whatever its goal, I doubt it was to make me feel what journalists and bloggers say they encounter every day—fear-induced self-censorship, suspicion of colleagues, and paranoia for their safety. Even I am not telling you everything. We arrive in Tashkent at 2 a.m. both bleary-eyed and wired. The airport looks like so many other post-Soviet airports we have flown into. Our six bags in tow, we are greeted at the exit by the same sorts of taxi drivers we’ve encountered outside countless train stations and airports throughout Eastern Europe, yelling as we pass, eager to charge twice or even five times the normal price of a fare to our hotel. But we are not your average Americans, who if they travel outside North America at all, go to places like London, Paris or Rome. Uzbekistan is our tenth post-Soviet country. My husband and I are here as part of a Fulbright grant from the U.S. State Department. My government is underwriting my research of independent media in post-Soviet countries, where freedom of the press is in its infancy in some countries and non-existent in others. I’m here to see where Uzbekistan falls on that spectrum. This posting follows nearly two years of my husband and I living in Ukraine, where I taught investigative reporting at various universities, and crisscrossed the former Soviet Union interviewing investigative reporters about the challenges they face to report the truth. Some of those journalists are now reporting from the war in Ukraine, others are in prisons in Belarus, and a few remain in hiding in Georgia and Azerbaijan. Now in Tashkent, my husband and I watch news of the fighting in Ukraine. Kyiv is always on our minds. My husband has family in Ukraine and in Belarus, which has joined in the war. I keep track of my former students in Ukraine, and we both correspond with former neighbors, friends and family who sleep in bomb shelters and spend their days cooking for soldiers or dodging bullets to deliver medical supplies. There’s so much about Tashkent that reminds me of Kyiv— the Soviet architecture, the broad streets and underground passages, the mixture of ethnic groups, the signs in Russian and English and the friendly people. I knew from earlier research that the Lenin statues had been torn down in Tashkent and that Uzbekistan’s president is pushing for modernization. The city is clean and well maintained. I love all the trees. But I am stunned when I stumble upon a statue of the Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko in front of a colorful Soviet mosaic on Shevchenko Street. In nearby Zulfiya Park, there is a statue of the Belarusian poet Yakub Kolas who only lived in Tashkent for three years. I learn that his image replaced that of the Uzbek poet and journalist Zulfiya for whom the park was named. Why take down a statue of a woman when so many countries are struggling to find women in history to honor? Why are Ukrainian and Belarusian poets honored in Tashkent? I wonder. “This is still an old Soviet town,” a local reporter explains. I hear her voice in my head as we encounter the same bureaucratic systems here that we experienced in Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan and others. The same systems that require lots of forms, registrations, stamps and standing in lines talking to people behind glass. The same demands for gratuities, like the mysterious charges a woman at the post office solicits of me and my husband without explanation but asks of no one else in line. Uzbeks, we are told, are known for being calm. They do seem calm. But last Sunday, my husband and I watched two men get out of their cars and punch each other because one man hadn’t sped through the intersection fast enough. Another guy stopped his car in the middle of the intersection and broke up the fight. In general, I find people in Tashkent polite and helpful. Sometimes these exchanges can be comical. Like the barista at a coffee shop who asked if I wanted “koritsa” with my cappuccino. “You’re asking me if I want a chicken with my coffee?” He smiled and nodded. Then he held up a silver canister to my nose. “Oh, cinnamon,” I said. “Yes, that’s nice.” Consulting Google translator, I learned that chicken is pronounced “kyritsa” and cinnamon is “koritsa.” Good to know. Now I fear I might accidentally ask for a pound of cinnamon at the grocery store. There are other surprises. Because of all the Russian and Belarusian immigrants who have fled here because of sanctions, finding an apartment was especially difficult. We had to pay 30 percent more for rent than initially advertised. Food in the grocery stores is three times more expensive than when I was in Ukraine. On average, I’m spending a little more than $100 a week in grocery stores and in the states I spent $200 a week on food. Restaurants are expensive too. While tasty plov is cheap and plentiful, restaurants like Thai, Italian, Korean and other ethnic foods, charge western prices. Cell phone coverage and taxis are cheap in Tashkent, but home goods are outrageously expensive. I tried to buy a printer, which in the states usually costs about $35 to $50. Here, the cheapest printer I found was $300. The same for other items like bedsheets and coffee grinders, both about double the average price in the states. Since I don’t speak Uzbek, I am delighted to see that many people speak Russian. There are far more fair-haired Europeans here than I expected. Yet I still stand out. When I try to communicate in my bumbling Russian, more times than not the waiter or store employee or the guy standing in line in front of me responds in excellent English. “Where are you from?” they always ask. When I say America, they marvel and tell me that it’s their dream to go there some day. I’ve heard this in so many countries and I am always curious what idyllic life they imagine we live in America. I always tried to rectify my Ukrainian students of this notion. America, I told them, is the land of 60-hour work weeks, two-week vacations, and health care premiums that costs more your monthly car payment. But even with the high cost of life in America, I’m grateful that my country was founded on the principle of freedom of speech. Our media has been practicing independently for centuries. We’ve made a lot of mistakes, but we’ve learned a few things. We’ve developed laws to protect journalists and carved out a set of ethics to make it clear when there is a conflict of interest. That’s why a fledging media in a country like yours is of interest to me. Since I arrived here three weeks ago, I’ve been talking to journalists at several independent media sites. Next week, I’ll be in Fergana to interview journalists there. Eventually I hope to travel to most of the major cities in Uzbekistan. I’ll be reporting my findings here. So, stay tuned. Adilov Sirojiddin, left, and Otabek Djuraev, are two bloggers in Uzbekistan who are pushing for free speech in their country. Meet the defenders of free speech in Uzbekistan: Gonzo-style bloggers. These are the folks who are testing the redlines of what writers and videographers in this country can report and post. These bloggers aggressively film wrongdoing, take up causes of people who pay them as well as those they feel driven to defend. They tend to be more outspoken and brazen than most journalists here.

Bloggers in Uzbekistan are a hybrid of western bloggers and influencers. While bloggers in the U.S. mostly write commentary and influencers mostly hawk products, here bloggers maintain popular news channels on social media, especially Telegram and Youtube, many with paid advertisements. The worst kind of bloggers here blackmail and extort people to pay them so that they don't post embarrassing videos or report about their corruption. The case of Otabek Sattoriy, a blogger convicted last year of defamation and extortion and now serving a six-and-a-half-year prison sentence, illustrates the tension between sanctioned (ie. controlled) journalism and rogue bloggers. On Wednesday, Sattoriy's appeal was heard in the Uzbekistan Supreme Court. His three lawyers each presented arguments that Sattoriy was exposing corruption and said the government's case against him was trumped up to stop his aggressive reporting. The three judge panel is reviewing the lawyers' arguments and will announce their decision next week. I'm told that Sattoriy's lower court hearings drew hordes of journalists. So I was surprised that there were less than a dozen media and mostly bloggers at Sattoriy's Supreme Court hearing. "We came because we want to prevent future cases for ourselves and other bloggers," explained Adilov Sirojiddin, a Youtube blogger with over 400,000 subscribers. He's also a reporter for Ezgulik, a human rights group. "If he’s made a mistake, we want to learn from this. There should be transparency in our country. We should be able to openly speak as journalists and bloggers and no prosecutors should prosecute us." There are no protections for bloggers in this country. The Agency for Mass Media—aka the government censors— dismiss bloggers as "active citizens." "There is nothing about bloggers in the legislation," Mamurjon Parpiev, head of media development at The Agency, told me. "Everyone who owns a telephone is a potential blogger. Thirty million people in Uzbekistan could be potential bloggers." Most bloggers here make the bulk of their money through advertisements on Youtube channels. In the past, most of those advertisements came from Russia, but with sanctions most Russian advertisements have stopped. "Bloggers are for sensation, loud speak. Others are looking for shock," Sirojiddin explains. "Those covering this hearing today are interested in the fate of Sattoriy. No one is paying us to be here." Otabek Djuraev, a Youtube blogger who has 352,000 followers, sees bloggers as more altruist, a kind of paid advocate. "Bloggers help people with basic problems," he said. "Bloggers get results for people who need help. I have helped many people because I can write what I want and I don't have to turn my story into a head editor who can kill it." I'm hearing a lot about editors in this country who kill stories because of threats from the security services (think Russian-styled KGB) in this country. And I'm hearing from journalists who are tired of fighting with such editors to get stories published. Djuraev and Sirojiddin say they don't hide that they ask for support from "businessmen and rich people." They are self-financed and pay for their own equipment, travel, hotel and fuel costs to cover stories all over the country. They argue that journalists have their own agendas and censor coverage, while bloggers stream entire events, providing hours of coverage. I found this to be true when I discovered that Sirojiddin posted an excruciatingly boring 12-minute video of me interviewing bloggers. Within 20 hours the post had 112 comments and more than 4,000 views. Many comments expressed bold, anti-government sentiments. If you want, you can check out the video here. Official journalists argue that these bloggers are not trained; they don't know the ethics of journalism; "it's just a business." This argument strikes me as hypocritical because editors at some of the most popular media sites regularly kill stories they fear will upset the government in order to stay in business—to keep making money. The government has taken several media outlets offline for days in the past and its security service routinely asks investigative reporters for "friendly chats." (More about this in a future post.) Some journalists here sympathize with editors who are pressured by the security services. This is the way it is in Uzbekistan, they argue. But I've interviewed many brave journalists in other post-Soviet countries with more draconian media restrictions—places like Belarus and Azerbaijan— who continue to report the truth even though they are regularly followed, harassed by the government and even imprisoned. Djuraev says he continues to writes what he believes is the truth even though he says he's been summoned to the prosecutor's office three times. My translator, Askar Djuraev, explained it this way: "When you think of journalists in this country, you think of people who work for the state. But bloggers are independent. They tell the truth." Many lawyers are afraid to take the cases of arrested bloggers and activists in Uzbekistan, but not Umidbek Davlatov. "I'm not intimidated," he told me. He said the only time he felt really threatened was when he handled the case an American citizen who was charged with terrorism. "Law enforcement tried to intimidate me. They took me into a separate room and threatened me." Afterwards, Davlatov revealed in a media interview what had happened. Davlatov got his client's charges reduced to a $50 fine and he was released.

He's hoping he can do something similar this week for his current client, Uzbekistan blogger Otabek Sattoriy, who is currently serving a six-and-half-year prison sentence on convictions of defamation and extortion. Davlatov says the case against his client was manufactured in retaliation for Sattoriy's aggressive reporting about corruption at the state-run gas company and his repeated criticism of local officials near Termez, on the border of Uzbekistan and Afghanistan. On March 30, Sattoriy's case is scheduled to appear before the three judge Supreme Court in Tashkent. The crimes alleged against Sattoriy seem small and hardly warranting such a long prison sentence. In December 2020, Sattoriy was filming a farmers' market when guards scuffled with him and broke his phone. Apparently he demanded his phone, valued at $436, be replaced. After he received a new phone he was charged with extortion. Additional charges of extortion and defamation were added when other people stepped forward claiming Sattoriy tried to blackmail them, too, unless they paid him. One of the charges involved Sattoriy asking that his parents be compensated after the government allowed a construction company to demolish their home to make way for an apartment building, a common problem in Uzbekistan. "All these arrests are due to his journalist activities," Davlatov insisted. "They are trying to stop too many journalists." He named four other bloggers who were detained by the government last week. Bloggers in this country are not considered or treated like journalists. They are not licensed or registered like official journalists. And often they take money to write about problems. "It's just a scheme to make money. It's a business," I heard one journalist and after another say. Many journalists here disdain bloggers, and nearly every journalist I have interviewed in this country believes Sattoriy is not innocent. "We investigated the Ottabek Sattoriy case," Abdukadirov Dilshod, editor in chief at Kun.uz, told me. Kun.uz is one of the more popular independent news sites in Tashkent and the outlet has faced its own battles with the government. In 2018, the government blocked their site for a week and fined them for writing about religious material without having the government's approval. But Kun.uz is not sympathetic to the plight of Sattoriy. "Sattoriy is guilty of violating the law," Dilshod said. "This is not a freedom of speech case and we are not taking his side." I heard similar accusations from other editors in Tashkent. Even Davlatov isn't crazy about the common practices of bloggers. "Bloggers will say anything. Sometimes they are not ethical. They don’t know ethics or the ethics of journalism. They made this a business and are not objective. They want to become Internet stars." Davlatov is a blogger himself. He shows me his Youtube channel. "I believe in journalism and in fighting corruption," he says. "If I know someone is innocent then I invite them to my own channel to be interviewed." Perhaps Davlatov will have a chance to invite his client Sattoriy after the Supreme Court hearing next week. Feruza Najmiddinova, deputy editor at Qalampir in Tashkent, stands before one of the walls at the news outlet dedicated to Uzbek domestic violence victims. She was the target of a sex video last year. On Friday I interviewed a young female journalist who seven months ago was threatened with a widely circulated sex video on social media. The video showed a woman having sex on a balcony with a man and claimed the woman was Feruza Najmiddinova, then a 29-year-old journalist working for the Qalampir news outlet in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Feruza had just published an article critical of restaurants in a business complex owned by the Mayor of Tashkent that were regularly breaking the 8 p.m. curfew during the city's Covid quarantine but were not fined by police.

Feruza is a married Muslim woman. This tactic of publicizing sex videotapes is popular in other Muslim countries, such as Azerbaijan, where Khadija Ismayilova, an investigative journalist, was also the target of such a video ten years ago. (See my story about Khadija in the Post.) In 2012, a blackmail video of Khadija having sex with her then-boyfriend surfaced on pro-government websites. Muslim women have been killed for shaming their families by having sex before marriage or with men who are not their husbands. When a close family member learned of the videotape, he was so angry at Khadija, he brought a knife to confront her. In Feruza's case, she was not the woman in the video, but the attempt to shame her publicly and pressure her to stop reporting on controversial subjects was still the intent of those who posted the video. Only in this case, that blackmail backfired. Instead of humiliating her, the video enraged the public. Many organizations, including several governmental bodies and other media organizations, came out and supported the journalist. Harassment on the Internet "remains one of the most disgusting ways to put pressure on journalists," Kamil Allamjanov, an Uzbekistan media ombudsmen told reporters at the time. "The more horrible a lie, the easier it is to believe it," he said. "The goal is to intimidate journalists and force them to resign." Even the President of Uzbekistan's daughter, Saida Mirziyoyeva, created a video message addressed to female journalists urging them not to give in to such blackmail. She ended her social media post with #IamFeruza. That hashtag went viral. Many other women and men began using it to show support for Feruza and female journalists. The outpouring of support forced the police to open an investigation into who made and distributed the the video, but so far nothing has been discovered. Feruza told me she never considered quitting her job as a journalist when the video came out, but her family fears that this kind of harassment and intimidation will end up hurting other family members and possibly Feruza's future children. Her husband, she said, worries about her and even before this incident warned her not to get into conflicts in her reporting. Her editor at Qalampir, Kamariddin Shaykhov, said he and other editors always feared that something like this might happen to one of their journalists. He never anticipated such widespread support, though. He fears that the next time someone tries to blackmail a journalist, the outrage might not be so vocal or widespread. Now whenever Feruza reports a story with conflict, the sex video weighs heavily on her mind, and she fears for her family. Seven months later she is still experiencing occasional intimidation on stories. Sometimes people post comments online, "Wasn't it better to be on the balcony?" or warning her: "Remember the balcony." The Feruza video scandal has had a chilling effect on other female journalists in Uzbekistan. One female journalist told me that whenever she is covering controversial stories, she's had subjects warn her, "Be careful, you don't want to become another Feruza." |

Fulbright in Central AsiaFrom March, 2022 to January of 2023, I was a Fulbright Scholar with the U.S. State Department in post-Soviet Central Asia. My previous Fulbright was in Ukraine. For the past six years, I have reported on journalists from post-Soviet countries who have experienced retaliation for reporting the truth. Archives

January 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed